I like to say that engineers make lousy politicians and politicians make lousy engineers. When we each try to do the other one’s job, it’s time to admit that we have a problem.

I like to say that engineers make lousy politicians and politicians make lousy engineers. When we each try to do the other one’s job, it’s time to admit that we have a problem.

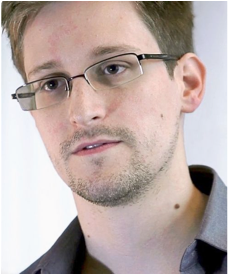

Even before the Paris attacks, the British Prime Minister David Cameron was already reacting to Apple and Google refusing to hold in escrow encryption keys necessary to decrypt data on their devices. In the wake of those attacks, the UK, the FBI and CIA directors have increased the drum beating. At the same time, some members of the technical community have come to conclude that the sun shines out of the posterior of Edward Snowden, and that all government requirements are illegitimate. This came to a remarkable climax in July when Snowden appeared at an unofficial event at the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) meeting in Prague.

A lot of the current heat being generated is over the notion of key escrow, where someone holds encryption keys such that private communications can be accessed under some circumstances, such as life or death situations or when a crime has been committed.

Now is the perfect time for both sides to take a deep breath, and to take stock of the current situation.

1. We cannot say whether any sort of encryption rules would have prevented the Paris attacks.

There are conflicting reports about whether or not the terrorists used encryption. What might have been is impossible to know, especially when we do not intimately know the decision makers, at least some of whom are now dead. We do know that Osama bin Laden refused to use a cell phone long before any of the Snowden revelations were made. He knew that he was being watched, and he knew that he had a technical disadvantage as compared to the U.S. eyes in the sky. It is a sure bet that even if these attackers didn’t use encryption, some attackers in the future will.

On the other hand, we also know that people tend to not secure their communications, even when the ability to do so is freely available. As a case and point, even though it has been perfectly possible to encrypt voice and email communications for decades, both continue to this day, and have been instrumental in unraveling the Petrobras scandal that rattled the Brazilian government.

2. Encryption is hard.

We’ve been trying to get encryption right for many decades, and still the best we can say is that we have confidence that for a time, the best encryption approaches are likely to be secure from casual attacks, and that is only when those approaches are flawlessly implemented. A corollary to this point is that almost all software and hardware programs have vulnerabilities. The probability of discovery of a vulnerability in any deployed encryption system approaches 100% over time. Knowing this, one test policy makers can apply regarding key escrow is whether they themselves would be comfortable with the inevitability that their most private personal communications being made public, or whether they would be comfortable knowing that some of their peers at some point in the future will be blackmailed to keep their communications private.

To make matters worse, once a technology is deployed, it may be out there for a very long time. Windows 95 is still out there, lurking in the corners of the network. It’s important to recognize that any risk that legislation introduces may well outlast the policy makers who wrote the rules. Because we are dealing with the core of Internet security, a “go slow and get it right” approach will be critical.

3. There are different forms of encryption, and some are easier to “back door” than others.

When we speak of encryption let us talk of two different forms: encryption of data in flight, such as when a web server sends you information or when you and your friends communicate on Skype, and encryption of data at rest, such as the files you save on your disk, or the information stored in your smart phone or tablet. Many enterprises implement key escrow mechanisms today for data at rest.

Escrowing keys of data in flight introduces substantial risks. Each communication uses session keys that exist for very short periods of time, perhaps seconds, and then are forgotten or destroyed. Unlike data at rest, escrowing of keys for encryption of data in flight has not been done at scale, and has barely been done at all. To retain such keys or any means to regenerate them would risk allowing anyone – bad or good – to reconstruct communications.

4. Engineers and scientists are both advisers and citizens. Policy makers represent the People.

It has been perfectly possible for Russia and the United States to destroy the world several times over, and yet to date policy makers have stopped that from happening. Because something is possible doesn’t necessarily mean it is something we do. Even for data at rest, any time a private key is required anywhere in the system it becomes a focal point for attack. But new functionality often introduces fragility. The question of whether it is worth fragility is inherently political and not technical.

The technical community that consists of scientists and engineers serve a dual role when it comes to deciding on the use of technology for a given purpose. First, they can advise policy makers as to the limits and tradeoffs of various technology. Members of the technical community are also citizens who have political views, just like other citizens. It’s important for that they make clear which voice they are speaking with.

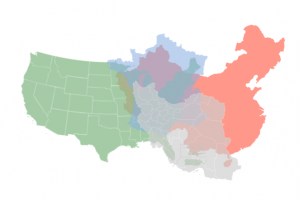

RFC 1984 famously makes the point that there is an inherent challenge with key escrow, that if one country mandates it, then other countries can also mandate it; and that there will be conflicts as to who should hold the keys and when they should be released. Those questions are important, and they are inherently political as well. To the left is a Venn diagram of just a handful of countries- the United States, Iran, China, and France. Imagine what that diagram would look like with 192 countries.

RFC 1984 famously makes the point that there is an inherent challenge with key escrow, that if one country mandates it, then other countries can also mandate it; and that there will be conflicts as to who should hold the keys and when they should be released. Those questions are important, and they are inherently political as well. To the left is a Venn diagram of just a handful of countries- the United States, Iran, China, and France. Imagine what that diagram would look like with 192 countries.

Professor Lawrence Lessig famously wrote that code (as in computer code) is law. While it is true in a natural sense that those who develop the tools we use can limit their use by their design, it is also the case that, to the extent possible, in a democratic society, it is the People who have the last word on what is law. Who else should get to decide, for instance, how members of society behave and how that behavior should be monitored and enforced? Who should get to decide on the value of privacy versus the need to detect bad behavior? In a democracy the People or their elected representatives make those sorts of decisions.

5. Perfect isn’t the goal.

Any discussion of security by its very nature involves risk assessment. How much a person spends on a door lock very much depends on the value of the goods behind the door and the perceived likelihood of attacker trying to open that door.

Some people in the technical community have made the argument that because bad guys can re-encrypt, no escrow solution is appropriate. But that negates the entire notion of a risk assessment. I suspect that many law enforcement officials would be quite happy with an approach that worked even half the time. But if a solution only works half the time, is it worth the risk that is introduced by new components in the system that include new central stores for many millions of keys? That is a risk assessment that needs to be considered by policy makers.

6. No one is perfectly good nor perfectly evil.

By highlighting weaknesses in the Internet architecture, Edward Snowden showed the technical community that we had not properly designed our systems to withstand pervasive surveillance. Whether we choose to design such a system is up to us. The IETF is attempting to do so, and there is good reason for that logic: even if you believe that the NSA is full of good people, if the NSA can read your communications, then others can do it as well, and may be doing so right now. And some of those others are not likely to fit anyone’s definition of “good”.

technical community that we had not properly designed our systems to withstand pervasive surveillance. Whether we choose to design such a system is up to us. The IETF is attempting to do so, and there is good reason for that logic: even if you believe that the NSA is full of good people, if the NSA can read your communications, then others can do it as well, and may be doing so right now. And some of those others are not likely to fit anyone’s definition of “good”.

On the other hand, while it is beyond an open secret that  governments spy on one another, Snowden’s release of information that demonstrated that we were successfully spying on specific governments did nothing more than embarrass those governments and harm U.S. relations with their leaders. Also, that the NSA’s capability was made public could have contributed to convincing ISIS to take stronger measures, but as I mentioned above, we will never know.

governments spy on one another, Snowden’s release of information that demonstrated that we were successfully spying on specific governments did nothing more than embarrass those governments and harm U.S. relations with their leaders. Also, that the NSA’s capability was made public could have contributed to convincing ISIS to take stronger measures, but as I mentioned above, we will never know.

So What Is To Be Done?

History tells us that policy made in a crisis is bad. The Patriot Act is a good example of this. So too was the internment of millions of Americans of Japanese descent in World War II. The birth of the Cold War gave birth of a new concept: McCarthyism.

And so my first bit of advice is this: let’s consult and not confront one another as we try to find solutions that serve the interests of justice and yet provide confidence in the use of the Internet. Policy makers should consult the technical community and the technical community should provide clear technical advice in return.

Second, let’s acknowledge each others’ expertise: people in law enforcement understand criminology. The technical community understands what is both possible and practicable to implement, and what is not. Policy makers should take all of this into account as they work with each of these communities and their constituents to find the right balance of interests.

Third, let’s recognize that this is going to take a while. When someone asserts that something is impossible or impracticable, we are left with research questions. Let’s answer them. Let’s be in it for the long haul and invest in research that tests what is possible and what is not. While not ultimate proof, researching various approaches will expose their strengths and weaknesses. Ultimate proof comes in the form of experience, or as my friends in the IETF like to say, running code. Even if we get beyond the technical issues involved with escrow, policy makers will have to answer the question as to who gets to hold the keys such that people can be reasonably assured that they’re only being released in very limited circumstances. That’s likely to be a challenging problem in and of itself.

Fourth, the law of unintended consequences applies. Suppose policy makers find common cause with a specific group of countries. The other countries are still going to want a solution. How will businesses cater to one group of countries but not another? Policy makers need to be aware that any sort of key escrow system may put businesses in an impossible situation.

Finally I would be remiss if I didn’t make clear that everyone has a stake in this game. Citizens are worried about privacy; governments are worried about security; industry is concerned about delivering products to market in a timely fashion that help the Internet grow and thrive. Bad guys also have interests. Sometimes we end up assisting them when we strike balances. What is important is that we do this consciously, and that when necessary, we correct that balance.

I love

I love  A lot of buzz went on in the past week over

A lot of buzz went on in the past week over