Some time ago I wrote about the difficulties that expatriates face when we calculate our taxes. As an American I don’t mind paying my fair share of taxes, even though I don’t live in the country, and even though America is practically the only supposedly-civilized society to tax non-resident citizens.

Some time ago I wrote about the difficulties that expatriates face when we calculate our taxes. As an American I don’t mind paying my fair share of taxes, even though I don’t live in the country, and even though America is practically the only supposedly-civilized society to tax non-resident citizens.

And as I wrote even more recently, I began the process in early March, trying to sort through this year’s paperwork. For those keeping track, this year’s taxes look to weigh in at about 350 grams, or just over 3/4 of a pound. Here are some things we expatriates have to do:

- Keep track of every day we spend in America for business. This is the chunk of change the U.S. gets. I think the idea is that someone shouldn’t live just across the border in Vancouver, for instance, and then commute to Washington.

- Don’t just assume Turbotax will do the right thing with the standard deduction. In fact, this isn’t just an expat thing: if you are subject to alternative minimum tax (AMT), the standard deduction is taxable, and so if you have some deductions it is sometimes better to itemize. The change from last year is that more expatriates pay AMT this year due to America’s deflated currency.

- Keep track of the largest sum in each foreign account for the year. This is because the Department of Treasury wants to know if we’re laundering money (we aren’t). This one is particularly important to manage because the government claims they can seize accounts for which information is not correctly reported. It’s also not made easy for investment accounts, where portfolio values vary by the day. This is a change from last year.

- Allocate deductions between those that are related to foreign income, and those that are not. The change from last year is that many could have used the standard deduction.

- Properly calculate exchange rates for both income and taxes paid or accrued. For those who have to do this, www.oanda.com has a lovely web site for this purpose. Perhaps the most annoying thing for expatriates is that many of the fields we fill in need to be converted to dollars. What’s more, in Europe it is not uncommon to have multiple currency accounts, making everything just a bit trickier. This is particularly true in Switzerland where some securities are only issued in euros.

And so, the average expatriate has to fill out the following forms:

- 1040 (no 1040a or -EZ);

- Schedules A, B, and possibly D.

- Four copies of Form 1116 for Foreign tax credit (general, passive) both normal and AMT;

- Two copies of Form 2555 for Foreign Income & Housing Exclusion;

- Form 2441 for children;

- Form 6251 for AMT;

- Treasury Form TD-F 90-22.1 for foreign bank accounts;

- a plethora of explanation statements for currency conversion and allocations.

If you own a home, there’s more paperwork. If you have other income, such as royalty income of some sort, you have more paperwork. If you have a disability, there’s more paperwork. If you have a home office, there’s more paperwork.

This is all for federal taxes. Nominally many states such as California would then like you to repeat the effort. If you have any deferred compensation from when you lived in the U.S., such as stock options, you will end up having to file state returns just to reclaim excess withholding. Some states want you to file for merely having attended a professional convention or conference (what some people call the basketball tax).

And so you might say, “Eliot, isn’t your time worth more than doing all of this paperwork?” No. The cost of accountants who prepare expatriate tax returns runs into the thousands of dollars for us, and ours is a relatively simple return. Often times employers will pay for these returns. If so, it’s a good deal for the employee.

Also, all of this does not take into account the taxes we must file in Switzerland. Here we do use an accountant. While my German has improved somewhat, each country has their own rules on where to fill in what column. I will say this about Zürich: they provide free copies of tax software to anyone who has to file.

The Wall Street Journal is reporting that a large Bitcoin exchange Coinbase has been served with a so-called “John Doe” warrant in search of those people attempting to evade taxes. A number of privacy advocates are upset at the breadth of the warrant, because it demands access for an entire broad class of people, and not specific people.

The Wall Street Journal is reporting that a large Bitcoin exchange Coinbase has been served with a so-called “John Doe” warrant in search of those people attempting to evade taxes. A number of privacy advocates are upset at the breadth of the warrant, because it demands access for an entire broad class of people, and not specific people. Some time ago

Some time ago

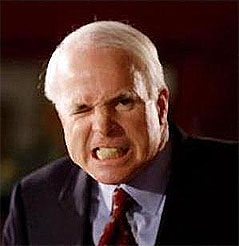

He was doing just fine at his lovefest in the Twin Cities, but then Senator John McCain started talking about cutting taxes.

He was doing just fine at his lovefest in the Twin Cities, but then Senator John McCain started talking about cutting taxes.  As I wrote earlier, he was palatable because he was talking about the least offensive tax, a corporate tax cut. As he takes a more offensive position by generalzing cuts, especially in light of news like the Federal Highway Fund running out of money, now I’m giving Obama the win for the economy, and McCain loses personality points for pandering.

As I wrote earlier, he was palatable because he was talking about the least offensive tax, a corporate tax cut. As he takes a more offensive position by generalzing cuts, especially in light of news like the Federal Highway Fund running out of money, now I’m giving Obama the win for the economy, and McCain loses personality points for pandering.