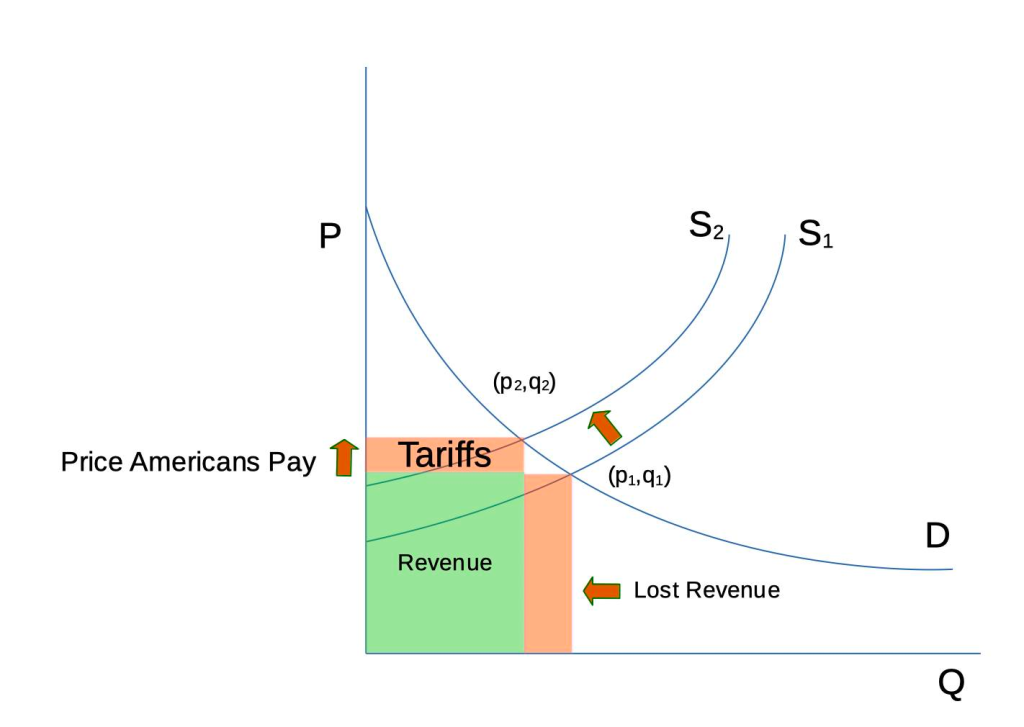

I’ve put together a basic, simplified graph to explain how tariffs work, and why Trump’s approach is going to harm consumers.

In the graph, P is the price of a product, and Q is the quantity people are willing to pay at a given price. Curve D represents consumers’ willingness to buy a product. At a given price, consumers are willing to buy a certain amount of a product. The higher the price, the lower the quantity of product that will be sold.

Curve S represents a price at which suppliers are willing to sell a product. The lower the price, the less willing a supplier is willing to sell, and the lower the quantity. Before tariffs, market pricing is at point (p1,q1).

Now the US introduces a tariff. This represents an upward shift in the supply curve from S1 to S2. That upsets the equilibrium and causes consumers to by fewer products at the higher price. So a new price and quantity (p2,q2) is set.

What has happened? The consumer has paid a higher price, the foreign producer has sold fewer products and taken in less revenue.

So what is Trump’s point? He’s hoping that by increasing consumer costs for imports, a domestic supplier will enter the market in the US that offers the same product at a price below p2. But it will not be so low as price p1 unless something else changes. Otherwise the product would not have been imported in the first place. That can happen for many reasons, such as the foreign producer delivering better quality product or lower cost, just to name two.

That means that no matter what happens, consumers in America will always be penalized for tariffs with higher prices than they otherwise would have paid. What’s more, because consumers would always end up paying higher prices for the same product, they’ll have less money to buy other things. And that leads to a further shrinkage of the economy.

Worse, those tariffs could work in reverse. Imagine a market in which raw materials such as lumber are imported to the US from Canada, it is turned into furniture, and shipped back to Canada. In this case, the tariffs are actually making US exports less competitive, encouraging Canadians to make their own furniture. The same concept would apply for tariffs on any raw material such as steel. In addition, there are some products that the US cannot produce such as the rare metals found in most computers.

Another aspect that the curve above doesn’t really show is startup cost. The first unit of any product is always the most expensive, because it required a production facility to be built. But if Trump’s policies get reversed, or he reverses them himself, then that startup cost turns into a loss. If you were a producer, would you trust that tariffs would remain in place?

Putting aside those startup costs, there’s another problem: the US unemployment rate is relatively low. Put another way, we wouldn’t have enough people to operate the factories Trump wants to see built. How to add people to the workforce? The safest way is to allow more immigration. Florida is considering another approach for their worker shortage: child labor.

Obviously there’s a lot more to this, and there are a lot of assumptions that we can review. In my view, doing so makes it clear that the economics of tariffs for America only make things worse.

The

The

Today’s Wall Street Journal

Today’s Wall Street Journal