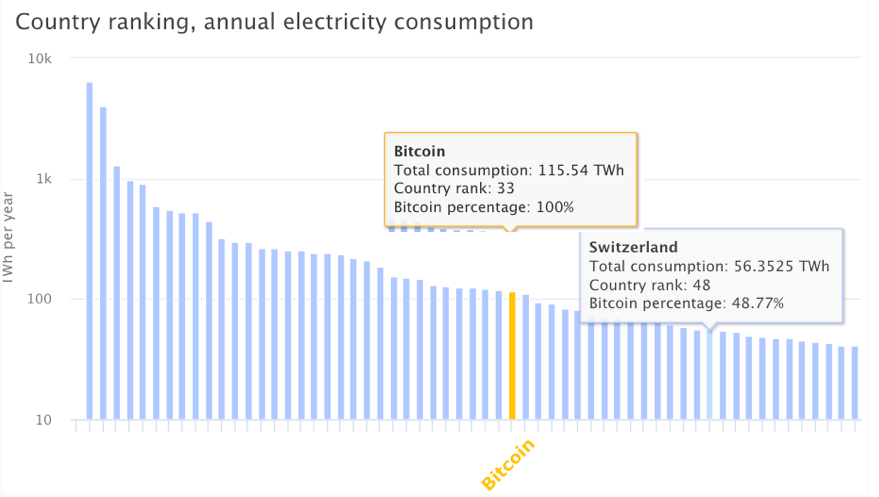

Imagine someone creating or supporting a technology that consumes vast amounts of energy only to produce nothing of intrinsic value and being proud of that of that fact. Such is the mentality of Bitcoin supporters. As the Financial Times reported several days ago, Bitcoin mining, the process by which this electronic fools’ gold is “discovered”, takes up as much power as a small country. And for what?

The euro, yen, and dollar are all tied to the fortunes and monetary policies of societies as represented by various governments. Those currencies are all governed by rules of their societies. Bitcoin is an attempt to strip away those controls. Some simply see cryptocurrencies as a means to disrupt the existing banking system, in order to nab a bit of the financial sector’s revenue. If so, right now they’re not succeeding.

In fact nothing about cryptocurrency is succeeding, while people waste a tremendous amount of resources. Bitcoin has been an empty speculative commodity and a vehicle for criminals to receive ransoms and other fees, as happened recently when the Colonial Pipeline paid a massive $4.4 million to DarkSide, a gang of cyber criminals.

What makes this currency attractive to hackers is that otherwise intelligent people purchase and promote the pseudo-currency. Elon Musk’s abrupt entrance and exit (that some might call Pump and Dump), demonstrates how fleeting that value may be.

Bitcoin is nothing more than an expression of what some would call crypto-governance, a belief that somehow technology is above it all and somehow is its own intrinsic benefit to some vague society. I call it cryptophilia: an unnatural and irrational love of all things cryptography, in an attempt to defend against some government, somewhere.

Cryptography As a Societal Benefit

Let’s be clear: Without encryption there could be no Internet. That’s because it would simply be too easy for criminals to steal information. And as is discussed below, we have no shortage of criminals. Today, thanks to efforts by people like letencrypt.org, the majority of traffic on the Internet is encrypted, and by and large this is a good thing.

This journey took decades, and it is by no means complete.

Some see encryption as a means by those in societies who lack basic freedoms as a means to express themselves. The argument goes that in free societies, governments are not meant to police our speech or our associations, and so they should have no problem with the fact that we choose to do so out of their ear shot, the implication being that governments themselves are the greatest threat to people.

Distilling Harm and Benefit

Bitcoin is an egregious example of how this can go very wrong. A more complicated case to study is the Tor network, which obscures endpoints through a mechanism known as onion routing. The proponents of Tor claim that it protects privacy and enables human rights. Critics find that Tor is used for illicit activity. Both may be right.

Back in 2016, Matthew Prince, the CEO of Cloudflare reported that, “Based on data across the CloudFlare network, 94% of requests that we see across the Tor network are per se malicious.” He went on to highly that a large portion of spam originated in some way from the Tor network.

One recent study by Eric Jardine and colleagues has shown that some 6.7% of all ToR requests are likely malicious activity. The study also asserts that so-called “free” countries are bearing the brunt of the cost of Tor, both in terms of infrastructure and crime. The Center for Strategic Studies quantifies the cost at $945 billion, annually, with the losses having accelerated by 50% over two years. The Tor network is key enabling technology for the criminals who are driving those costs, as the Colonial Pipeline attack so dramatically demonstrated.

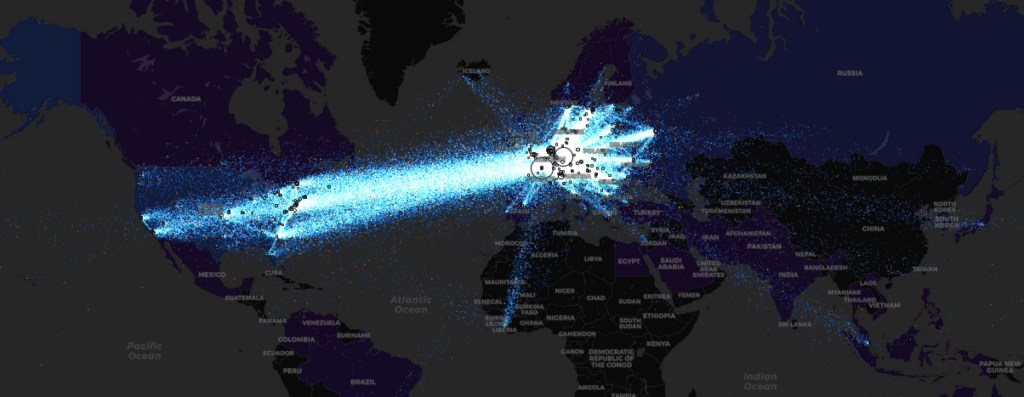

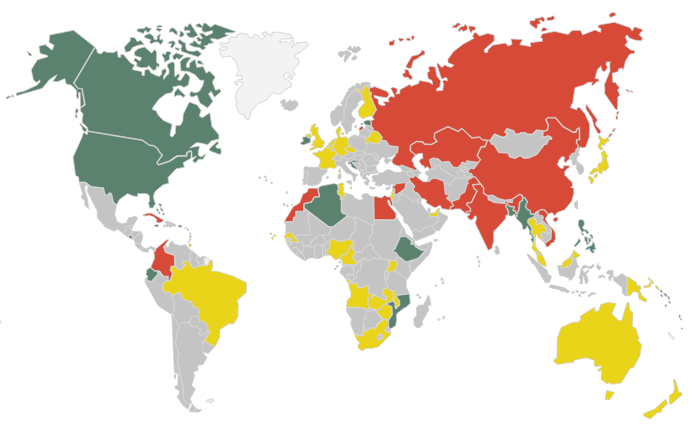

Each dot on the diagram above demonstrates a waste of resources, as packets make traversals to mask their source. Each packet may be routed and rerouted numerous times. What’s interesting to note is how dark Asia, Africa, and South America were.

While things have improved somewhat since 2016, bandwidth in many of these regions still comes at a premium. This is consistent with Jardine’s study. Miscreants such as DarkSide are in those dots, but so too are those who are seeking anonymity for what you might think are legitimate reasons.

One might think that individuals have not been prosecuted for using encrypted technologies, but governments have been successful in infiltrating some parts of the so-called dark web. A recent takedown of a child porn ring followed a large drug bust last year by breaking into Tor network sites is enlightening. First, one wonders how many other criminal enterprises haven’t been discovered. As important, if governments we like can do this, so can others. The European Commission recently funded several rounds of research into distributed trust models. Governance was barely a topic.

Other Forms of Cryptophilia: Oblivious HTTP

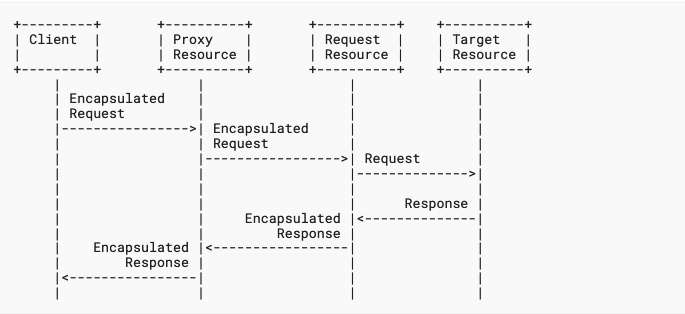

A new proposal known as Oblivious HTTP has appeared at the IETF that would have proxies forward encrypted requests to web servers, with the idea of obscuring traceable information about the requestor.

This will work with simple requests a’la DNS over HTTP, but as the authors note, there are several challenges. The first is that HTTP header information, which would be lost as part of this transaction, actually facilitates the smooth use o the web. This is particularly true with those evil cookies about which we hear so much. Thus any sort of session information would have to be re-created in the encrypted web content, or worse, in the URL itself.

Next, there is a key discovery problem: if one is encrypting end-to-end, one needs to have the correct key for the other end. If one allows for the possibility of receiving such information using non-oblivious methods to the desired web site, then it is possible to obscure the traffic in the future. But then an interloper may know at least that the site was visited once.

The other challenge is that there is no point of obscuring the information if the proxy itself cannot be trusted, and it doesn’t run for free: someone has to pay its bills. This brings us back to Jardine, and who is paying for all of this.

Does encryption actually improve freedom?

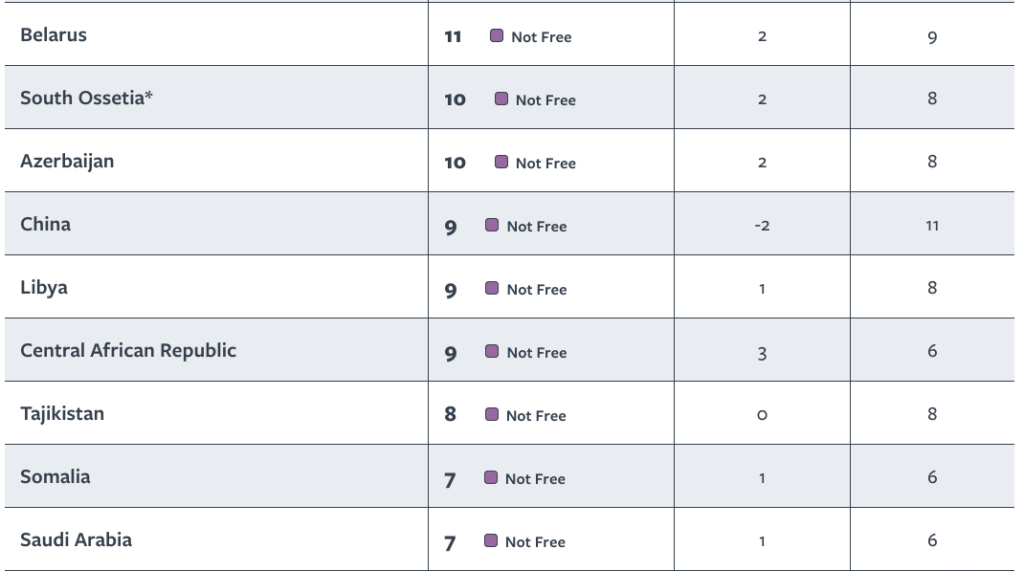

Perhaps the best measure of whether encryption has improved freedoms can be found in the place with the biggest barrier to those freedoms on the Internet: China. China is one of the least free countries in the world, according to Freedom House.

Another view of the same information comes from Global Partners Digital:

Paradoxically, one might answer the question that freedom and encryption seem to go hand in glove, at least to a certain point. However, the causal effects seem to indicate that encryption is an outgrowth of freedom, and not the other way around. China blocks the use of Tor, as it does many sites through its Great Firewall, and there has been no lasting documented example that demonstrates that tools such as Tor have had a lasting positive impact.

On the other hand, to demonstrate how complex the situation is, and why Jardine’s (and everyone else’s) work is so speculative, it’s not like dissidents and marginalized people are going to stand up for a survey, and say, “Yes, here I am, and I’m subverting my own government’s policies.”

Oppression as a Service (OaaS)

Cryptophiliacs believe that they can ultimately beat out, or at least stay ahead of the authorities, whereas China has shown its great firewall to be fully capable of adapting to new technologies over time. China and others might also employ another tactic: persisting meta-information for long periods of time, until flaws in privacy-enhancing technology can be found.

This gives rise to a nefarious opportunity: Oppression as a Service. Just as good companies will often test out new technology in their own environments, and then sell it to others, so too could a country with a lot of experience at blocking or monitoring traffic. The price they charge might well depend on their aims. If profit is pure motive, some countries might balk at the price. But if ideology is the aim, common interest could be found.

For China, this could be a mere extension of its Belt and Road initiative. Cryptography does not stop oppression. But it may – paradoxically – stop some communication, as our current several Internets continue to fragment into the multiple Internets that former Google CEO Eric Schmidt raised in 2018 thought he was predicting (he was really observing).

Could the individual seeking to have a private conversation with a relative or partner fly under the radar of all of this state mechanism? Perhaps for now. VPN services for visitors to China thrive; but those same services are generally not available to Chinese residents, and the risks of being caught using them may far outweigh the benefits.

Re-establishing Trust: A Government Role?

In the meantime, cyber-losses continue to mount. Like any other technology, the genie is out of the bottle with encryption. But should services that make use of it be encouraged? When does its measurable utility become more a fetish?

By relying on cryptography we may be letting ourselves and others off the hook for their poor behavior. When a technical approach to enable free speech and privacy exists, who says to a miscreant country, “Don’t abuse your citizens”? At what point do we say that, regardless, and at what point do democracies not only take responsibility for their own governments’ bad behavior, but also press totalitarian regimes to protect their citizens?

The answer may lie in the trust models that underpin cryptography. It is not enough to encrypt traffic. If you do so, but don’t know who you are dealing with on the other end, all you have done is limited your exposure to that other end. But trusting that other end requires common norms to be set and enforced. Will you buy your medicines from just anyone? And if you do and they turn out to be poisons, what is your redress? You have none if you cannot establish rules of the Internet road. In other words, governance.

Maybe It’s On Us

Absent the sort of very intrusive government regulation that China imposes, the one argument that cryptophiliacs have in their pocket that may be difficult for anyone to surmount is the idea that, with the right tools, the individual gets to decide this issue, and not any form of collective. That’s no form of governance. At that point we had better all be cryptophiliacs.

We as individuals have a responsibility to decide the impact of our decisions. If buying a bitcoin is going to encourage more waste and prop up criminals, maybe we had best not. That’s the easy call. The hard call is how we support human rights while at the same time being able to stop attacks on our infrastructure, where people can die as a result, but for different reasons.

Editorial note: I had initially misspelled cryptophilia. Thanks to Elizabeth Zwicky for pointing out this mistake.