In the technical community we like to say that the Internet is a network of networks, and that each network is independently operated and controlled. That may be true in some technical sense, but it far from the pragmatic truth.

Today’s New York Times contains an editorial that supports former Google CEO Eric Schmidt’s view that the Internet will balkanize into two – one centered around US/Western values and one around values of China, and indeed it goes farther, to state that there will be three large Internets, where Europe has its own center.

The fact is that this is the world in which we already live. It is well known that China already has its own Internet, in which all applications can be spied by the government. With the advent of the GDPR, those of us in Europe have been cut off from a number of non-European web sites because they refuse to comply with Europe’s privacy regulations. For example, I cannot read the Los Angeles Times from Switzerland. I get this lovely message:

Unfortunately, our website is currently unavailable in most European countries. We are engaged on the issue and committed to looking at options that support our full range of digital offerings to the EU market. We continue to identify technical compliance solutions that will provide all readers with our award-winning journalism.

And then there are other mini-Internets, such as that of Iran, in which they have attempted to establish their own borders, not only to preserve their culture, but also their security, at least in their view, thanks to such attacks as Stuxnet.

If China can make its own rules, and Europe can establish its own rules, and the U.S. has its own rules, and Iran has its own rules, can we really say that there is a single Internet today? And how many more Internets will there be tomorrow?

The trend is troubling.

We Internet geeks also like to highlight The Network Effect, in which the value of the network to each individual increases based on the number of network participants, an effect first observed with telephone networks. There is a risk that it can operate in reverse: each time the network bifurcates, its value to each participant decreases because of the loss of the participants who are now on separate networks.

Ironically, the capabilities found in China’s network may be very appealing to other countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, just as shared values around the needs of law enforcement had previously meant that a single set of lawful intercept capabilities exists in most telecommunications equipment. This latter example reflected shared societal values of the time.

If you believe that the Internet is a good thing on the whole, then a single Internet is therefore preferable to many bifurcated Internets. But that value is, at least for the moment, losing to the divergent views that we see reflected in the isolationist policies of the United States, the unilateral policies of Europe, BREXIT, and of course China. Unless and until the economic effects of the Reverse Network Effect are felt, there is no economic incentive for governments to change their direction.

But be careful. A new consensus may be forming that some might not like: a number of countries seemingly led by Australia are seeking ways to gain access to personal devices such as iPhones for purposes of law enforcement, with or without strong technical protections. Do you want to be on that Internet, and perhaps as importantly, will you have a choice? Perhaps there will eventually be one Internet, and we may not like it.

One thing is certain: At least for a while, won’t be reading the LA Times.

My views do not necessarily represent those of my employer.

* Artwork: By ProjectManhattan, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39714913

When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top:

When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top:

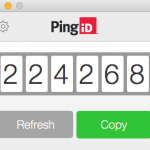

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from