Bloomberg has reported that a company, Supre Micro, Inc., has had their hardware hacked, maybe with the knowledge or encouragement of the Chinese government. Impacted customers reportedly include Apple Computer and Amazon, who may have had their data centers compromised. Apple, Amazon, and Super Micro Inc have all issued strong denials.

The attack as described involves a tiny chip being surreptitiously inserted on the board of one of Super Micro Inc’s suppliers. According to the report, the chip could insert code that would allow for malware to be installed. We’ll come back to how to address that attack at a later date.

While this attack is at least feasible in theory, and while it is possible for vendors to keep a secret, and indeed it has enraged many people in the past that a bunch of vendors have kept secrets for quite a while, here we have a report where we have denials all around, and yet we have a somewhat detailed description of the attack. There are only three possibilities:

- The reporters and their sources are accurate; in which case there is a MASSIVE conspiracy that includes Apple and Amazon, not to mention government officials.

- The reporters are wrong, and have been fed corroborated yet false information by government sources.

- The reporters are fabricating a story.

An existence proof – one board – would suffice to show that (1) is true. Proving (2) would be quite difficult without recorded conversations of confidential sources. (3) is also difficult to prove.

Let’s hope the reporters are fabricating the story, because the alternatives are far worse. If the reporters are accurate, we either have vendors standing on their heads or government sources feeding media a pack of lies. Furthermore, although China has broken into the computers of adversaries in the past, it would be particularly bad for false accusations to circulate that could later be used to discredit or tarnish those that are true.

More to come.

When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top:

When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top:

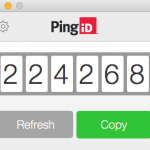

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from  You may recall that I am working on a mechanism known as

You may recall that I am working on a mechanism known as