How can the network protect so many types of things? We need for manufacturers to step up and tell us.

Since 2011 Cisco Systems has been forecasting that there will be at Since least 50 billion devices connected to the Internet by the year 2020. Those are a lot of Things. but that’s not the number I’m worried about. Consider this: Apple manages somewhere in the neighborhood of 1 billion active iOS devices on their own, and there are about 1.4 billion Android devices that are also managed, though less well. Rather, it’s the number of types of things that people should be concerned about. To begin with,not everyone is going to do such a great job at managing their products out in the field as Apple and Google do. Moreover, even Apple and Google end support for different versions of their products after some period of time.

Since 2011 Cisco Systems has been forecasting that there will be at Since least 50 billion devices connected to the Internet by the year 2020. Those are a lot of Things. but that’s not the number I’m worried about. Consider this: Apple manages somewhere in the neighborhood of 1 billion active iOS devices on their own, and there are about 1.4 billion Android devices that are also managed, though less well. Rather, it’s the number of types of things that people should be concerned about. To begin with,not everyone is going to do such a great job at managing their products out in the field as Apple and Google do. Moreover, even Apple and Google end support for different versions of their products after some period of time.

I call this the Internet of Threats. Each and every one of those devices, including the device you are reading this note on right now, probably has a vulnerability that some hacker will exploit.

A good number of the manufacturers of those things will never provide fixes to their customers, and even those that do have very little expectation that the device will ever be updated. Let’s put it this way: when was the last time you installed new software on your printer? Probably never.

The convenient thing is that many Things probably only have a small set of uses. A printer prints and maybe scans, thermostat like a Nest controls the temperature in your house, and a baby monitor monitors babies. This is the exact opposite of the general purpose computing operating model that your laptop computer has, and we can take advantage of that fact.

If a Thing only has a small number of uses, then it  probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.

probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.

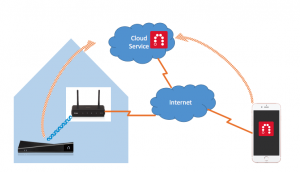

So what is needed to make all of this work? Again, conveniently most of the components are already in your network. The first thing we need is a way for devices to tell the network where to get the manufacturer usage description file (or MUD file). There’s an excellent example of that in your browser right now, called a Universal Resource Locator (URL), like https://www.ofcourseimright.com. In our case, we need something a bit mroe structured, like https://www.example.com/.well-known/mud/v1/someproduct/version. How you get that file, however, is exactly the same as how you got to this web page.

Next, we need a way for the Thing to give the URI to the network. Once again, the technology is pretty much done. Your device got an IP address today using Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP), which provides an introduction between the device and the network. All we need to do is add one new parameter or option so that the client can simply pass along this MUD URI. There are even more secure ways of doing that using public key infrastructure (PKI) approaches such as IEEE’s 802.1AR format and 802.1X protocol. The nice thing about using a manufacturer certificate in 802.1AR is that it is then the manufacturer and not the device itself that is asserting what the device communication patterns are.

Now, thanks to DHCP or IEEE 802.1X, the network can go get the MUD file. What does that look like? At the moment, <it> <looks> <like> <a> <bunch> of <XML>. {“it” , [“may”, “look”, “more”], “like, {“json”}} in the future. The good news here is that once again, we’re building on a bunch of work that is already complete. The XML itself is structured using a data model called YANG. So long as it conveys to the network what sort of protections a device needs, it could be anything, but YANG will do for now.

Finally, the basic enforcement building block is the access control function in a router or access point. That function says what each device can communicate with, and they’ve been around since the earliest days of the Internet.

And that’s it. So now if I have printer from HP and they make a MUD file available, they might tell my network that they only want to receive printer communications, and that the printer should only ever try to send certain types of unsolicited messages. If anyone tries to contact the printer for another use, forget it. If the printer tries to contact CNN – or more importantly random devices on my network, it’s probably been hacked and it will be blocked. Google can do the same with a Nest.

We’re talking about this at the IETF and elsewhere. What do you think?

[Updated thanks to an old friend.]

[Updated thanks to an old friend.] Since 2011

Since 2011  probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.

probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.