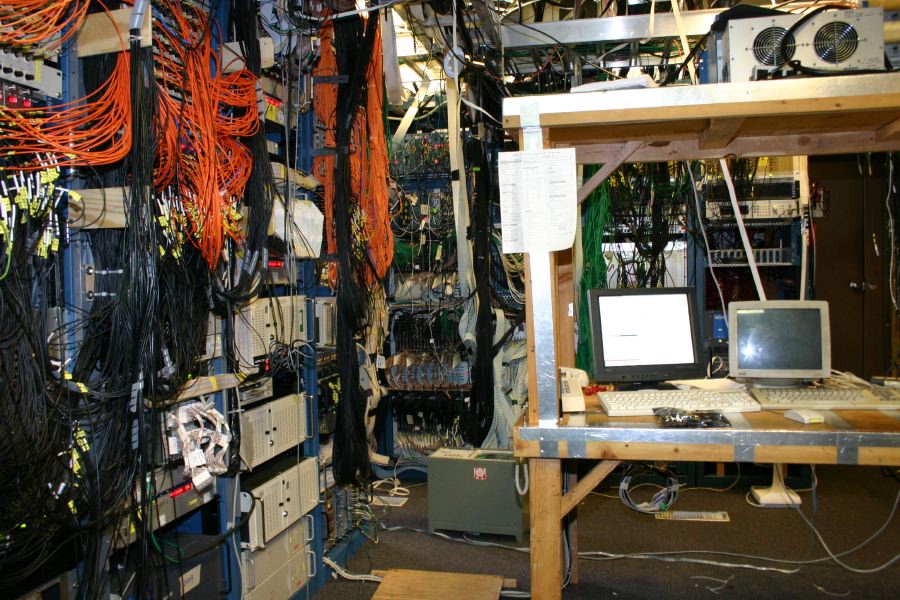

In the summer of 2004 I gave an invited talk at the USENIX Technical Symposium entitled “How Do I Manage All Of This?” It was a plea to the academics that they ease off of new features and figure out how to manage old ones. Just about anything can be managed if you spend enough time. But if you have enough of those things you won’t have enough time. It’s a simple care and feeding argument. When you have enough pets you need to be efficient about both. Computers, applications, and people all require care and feeding. The more care and feeding, the more chance for a mistake. And that mistake can be costly. According to one Yankee Group study in 2003, between thirty and fifty percent of all outages are due to configuration errors. When asked by a reporter what I believed the answer was to dealing with complexity in the network, I replyed simply, “Don’t introduce complexity in the first place.”

In the summer of 2004 I gave an invited talk at the USENIX Technical Symposium entitled “How Do I Manage All Of This?” It was a plea to the academics that they ease off of new features and figure out how to manage old ones. Just about anything can be managed if you spend enough time. But if you have enough of those things you won’t have enough time. It’s a simple care and feeding argument. When you have enough pets you need to be efficient about both. Computers, applications, and people all require care and feeding. The more care and feeding, the more chance for a mistake. And that mistake can be costly. According to one Yankee Group study in 2003, between thirty and fifty percent of all outages are due to configuration errors. When asked by a reporter what I believed the answer was to dealing with complexity in the network, I replyed simply, “Don’t introduce complexity in the first place.”

It’s always fun to play with new toys. New toys sometimes require new network features. And sometimes those features are worth it. For instance, the ability to consolidate voice over data has brought a reduction in the amount of required physical infrastructure. The introduction of wireless has meant an even more drastic reduction. In those two cases, additional configuration complexity was likely warranted. In particular you’d want to have some limited amount of quality-of-service capability in your network.

Franciscan friar William of Ockham first articulated a principle in the 14th century that all other things being equal, the simplest solution is the best. We balance that principle with a quote from Einstein who said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Over the next year I will attempt to highlight examples of where we have violated both of these statements, because they become visible in the public press.

Until then, ask yourself this: what functionality is running on your computer right now that you neither need nor want? That very same functionality is a potential vulnerability. And what tools reduce complexity? For instance, here is some netstat output:

% netstat -an|more Active Internet connections (servers and established) Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:993 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:995 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:3306 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:587 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:110 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:111 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:2544 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN tcp 0 0 127.0.0.1:817 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:32768 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 127.0.0.1:53 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:69 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:111 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:631 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 127.0.0.1:123 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:123 0.0.0.0:* udp 0 0 :::32769 :::* udp 0 0 fe80::219:dbff:fe31:123 :::* udp 0 0 ::1:123 :::* udp 0 0 :::123 :::*

It’s difficult for an expert all of this stuff. Heaven help all of us who aren’t experts. So what do we do? We end up running more programs to identify what we were running. In other words? That’s right. Additional complexity. What would have happened if we simply had the name of the program output with that line? This is what lsof does, and why it is an example of reducing complexity through innovation. Here’s a sample:

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE NODE NAME xinetd 3837 root 5u IPv4 10622 TCP *:pop3 (LISTEN) xinetd 3837 root 8u IPv4 10623 TCP *:pop3s (LISTEN) xinetd 3837 root 9u IPv4 10624 UDP *:tftp named 3943 named 20u IPv4 10695 UDP localhost:domain named 3943 named 21u IPv4 10696 TCP localhost:domain (LISTEN) named 3943 named 24u IPv4 10699 UDP *:filenet-tms named 3943 named 25u IPv6 10700 UDP *:filenet-rpc named 3943 named 26u IPv4 10701 TCP localhost:953 (LISTEN) named 3943 named 27u IPv6 10702 TCP localhost:953 (LISTEN) ntpd 4026 ntp 16u IPv4 10928 UDP *:ntp ntpd 4026 ntp 17u IPv6 10929 UDP *:ntp ntpd 4026 ntp 18u IPv6 10930 UDP localhost:ntp

Often times it is said that the purpose of academic research is to seek the truth, no matter where it leads. The purpose of industry representatives is often to obscure the truths they do not like. Such apparently was the case at a recent hearing of the Texas House of Representatives’

Often times it is said that the purpose of academic research is to seek the truth, no matter where it leads. The purpose of industry representatives is often to obscure the truths they do not like. Such apparently was the case at a recent hearing of the Texas House of Representatives’  When I was about 13 years old, my neighbors put a pool in their back yard. However, they failed to put a fence around it. My sister at the time was only four years old, and there were many people her age in the neighborhood. In our community there was an ordinance that required such fences, but the neighbors ignored it, as they did my parents’ pleas.

When I was about 13 years old, my neighbors put a pool in their back yard. However, they failed to put a fence around it. My sister at the time was only four years old, and there were many people her age in the neighborhood. In our community there was an ordinance that required such fences, but the neighbors ignored it, as they did my parents’ pleas. Have you ever received a notice that your data privacy has been breached? What the heck does that mean anyway? Most of the time what it means is that some piece of information that you wouldn’t normally disclose to others, like a credit card or your social security number, has been released unintentionally, and perhaps maliciously (e.g., stolen). About five years ago states began passing data breach privacy laws that required authorized possessors of such information to report to victims when a breach occurred. There were basically two goals for such laws:

Have you ever received a notice that your data privacy has been breached? What the heck does that mean anyway? Most of the time what it means is that some piece of information that you wouldn’t normally disclose to others, like a credit card or your social security number, has been released unintentionally, and perhaps maliciously (e.g., stolen). About five years ago states began passing data breach privacy laws that required authorized possessors of such information to report to victims when a breach occurred. There were basically two goals for such laws: