New York is proposing new cybersecurity rules that would raise the bar for banks over which they have jurisdiction (wouldn’t that be just about all of them?). On their face, the new regulations would seem to improve overall bank posture, but digging a bit deeper leads me to conclude that these regulations require a bit of work.

A few key new aspects of the new rules are as follows:

- Banks must perform annual risk assessments and penetration tests;

- New York’s Department of Financial Services (DFS) must be notified within 72 hours of an incident (there are currently numerous timeframes);

- Banks must use 2-factor authentication for employee access; and

- All non-public data must be encrypted, both in flight and at rest.

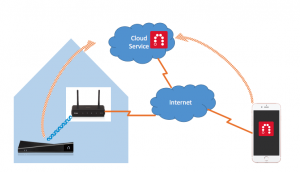

The first item on that list is what Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) already get paid to do. Risk assessment is in particular the most important task on this list, because as banks evolve their service offerings, they must ascertain both evolving threats and potential losses. For example, as banks added iPhone apps, the risk of an iPhone being stolen became relevant, thus impacting app design.

Notification laws exist already in just about all jurisdictions. The proposed banking regulation does not say what the regulator will do with the information or how it will be safeguarded. A premature release can harm ongoing investigations.

Most modern banks outside the United States already use two-factor authentication for employee access, and many require two-factor authentication for customer access.

That last one is a big deal. Encrypting data in flight (e.g., transmissions from one computer to another) protects against eavesdroppers. At the same time, absent other controls, encryption can obscure data exfiltration (information theft). Banks currently have many tools that rely on certain transmissions being “in the clear”, and it may require some redesign of communication paths to address both the encryption in flight requirement and auditing needs. Some information is simply impractical today to encrypt in flight. This includes discovery protocols such as DHCP, name service exchanges (DNS), and certain other network functions. To encrypt much of this information would require yet lower layer protection such as IEEE 802.1AE (MACSEC) hop-by-hop encryption. The regulation is, again, vague on precisely what is necessary. One thing is clear, however: their definition of non-public information is quite broad.

To meet the “data at rest” requirement banks will either have to employ low level disk encryption or higher level object-level encryption. Low level encryption protects against someone stealing a disk or taking it from the trash and reading it, but provides very little protection against someone breaking into a computer when the disk is still spinning. Moreover, banks generally have rules about crushing disks before they can leave a data center. Requiring data at rest to be encrypted in data centers may not provide much risk mitigation. While missing laptops have repeatedly been a source data breaches, how often has a missing data center disk caused a breach?

Object-level encryption, or the encryption of groups of information elements (think Email messages) can provide strong protection should devices be broken into. Object-level encryption is particularly interesting because if done right, it can address both data in flight and data at rest. The challenge with object-level encryption is that the tools for it are quite limited. While there are some tools such as email message encryption, and while there are various ways one can use existing general purpose mechanisms such as OpenSSL to encrypt objects at rest, on object-level encryption remains a challenge because it must be implemented at the application level across all applications. Banks may have tens of thousands of applications running at any one time.

This is an instance where the financial industry could be a technology leader. However, all such development must be grounded in a proper risk assessment. Otherwise we end up in a situation where banks will have expended enormous amounts of resources without having substantially improved security.

Since 2011

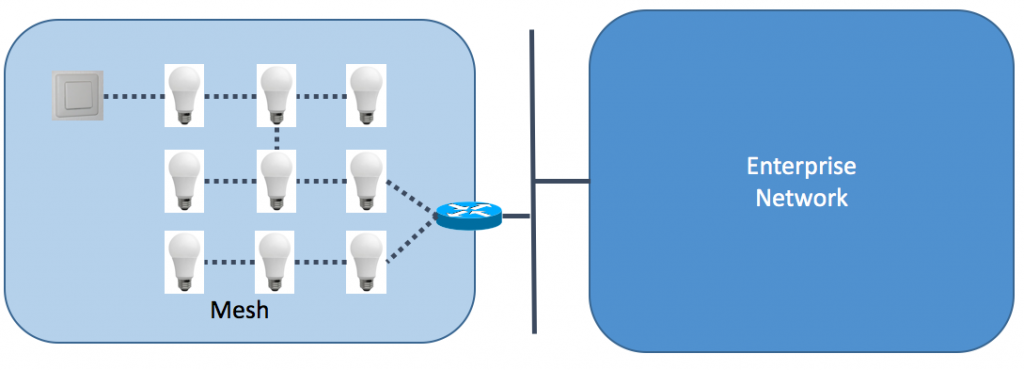

Since 2011  probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.

probably only communicates on the network in a small number of ways. The people who know about those small number of ways are most likely the manufacturers of the devices themselves. If this is the case, then what we need is a way for manufacturers to tell firewalls and other systems what those ways are, and what ways are particularly unsafe for a device. This isn’t much different from a usage label that you get with medicine.