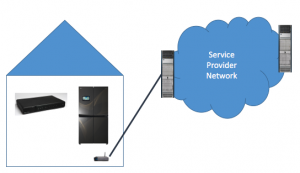

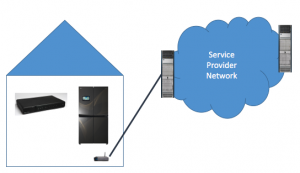

The attack on DNS provider DYN’s infrastructure that took down a number of web sites is now old news. While not all the facts are public, the press reports that once again, IoT devices played a significant role. Whether that it is true or not, it is a foregone conclusion that until we address security of these devices, such attacks will recur. We all get at least two swings at this problem: we can address the attacks from Things as they happen and we can work to keep Things secure in the first place.

What systems do we need to look at?

- End nodes (Cameras, DVRs, Refrigerators, etc);

- Home and edge firewall systems;

- Provider network security systems;

- Provider peering edge routers; and

- Infrastructure service providers (like DYN)

In addition, researchers, educators, consumers and governments all have a role to play.

What do the providers of each of those systems need to do?

What follows is a start at the answer to that question.

Endpoints

It’s easy to pin all the blame on the endpoint developers, but doing so won’t buy so much as a cup of coffee. Still, thing developers need to do a few things:

- Use secure design and implementation practices, such as not hardcoding passwords or leaving extra services enabled;

- Have a means to securely update their systems when a vulnerability is discovered;

- Provide network enforcement systems Manufacturer Usage Descriptions so that the networks can enforce policies around how a device was designed to operate.

Home and edge firewall systems

There are some attacks that only the network can stop, and there are some attacks that the network can impede. Authenticating and authorizing devices is critical. Also, edge systems should be quite leery of devices that simply self-assert what sort of protection they require, because a hacked device can make such self-assertions just as easily as a healthy device. Hacked devices have recently been taking advantage of a gaming mechanism in many home routers known as Universal Plug and Play (uPnP) which permits precisely the sorts of self-assertions should be avoided.

Provider network security systems

Providers need to be aware of what is going on in their network. Defense in depth demands that they observe their own networks in search of malicious behavior, and provide appropriate mitigations. Although there are some good tools out there from companies like Cisco such as Netflow and OpenDNS, this is still a pretty tall order. Just examining traffic can be capital-intensive, but then understanding what is actually going on often requires experts, and that can get expensive.

Provider peering edge routers

The routing system of the Internet can be hijacked. It’s important that service providers take steps to prevent that from happening. A number of standards have been developed, but service providers have been slow to implement for one reason or another. It helps to understand the source of attacks. Implementing filtering mechanisms makes it possible for service providers to establish accountability for the sources of attack traffic.

Infrastructure providers

Infrastructure upon which other Internet systems rely needs to be robust in the face of attack. DYN knows this. The attack succeeded anyway. Today, I have little advice other than to understand each attack and do what one can to mitigate it the next time.

Consumers

History has shown that people in their homes cannot be made to do much to protect themselves in a timely manner. Is it reasonable, for instance, to insist that a consumer to spend money to replace an old system that is known to have vulnerabilities? The answer may be that it depends just how old that system really is. And this leads to our last category…

Governments

Governments are already involved in cybersecurity. The question really is how involved with they get with IoT security. If the people who need to do things aren’t doing them, either we have the wrong incentive model and need to find the right one, or it is likely that governments will get heavily involved. It’s important that not happen until the technical community has some understanding as to the answers of these questions, and that may take some time.

Governments are already involved in cybersecurity. The question really is how involved with they get with IoT security. If the people who need to do things aren’t doing them, either we have the wrong incentive model and need to find the right one, or it is likely that governments will get heavily involved. It’s important that not happen until the technical community has some understanding as to the answers of these questions, and that may take some time.

And so we have our work cut out for us. It’s brow furrowing time. As I wrote above, this was just a start, and it’s my start at that. What other questions need answering, and what are the answers?

Your turn.

Photo credits:

Capitol by Deror Avi – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Router by Weihao.chiu from zh, CC BY-SA 3.0

DVR by Kabel Deutschland, CC BY 3.0

Router by Cisco systems – CC BY-SA 1.0

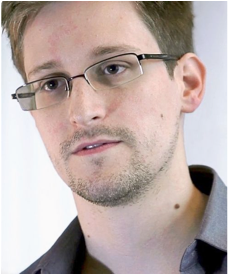

When Edward Snowden disclosed the NSA’s activities, many people came to realize that network systems can be misused, even though this was always the case. People just realized what was possible. What happened next was a concerted effort to protect protect data from what has become known as “pervasive surveillance”. This included development of a new version of HTTP that is always encrypted and an easy way to get certificates.

When Edward Snowden disclosed the NSA’s activities, many people came to realize that network systems can be misused, even though this was always the case. People just realized what was possible. What happened next was a concerted effort to protect protect data from what has become known as “pervasive surveillance”. This included development of a new version of HTTP that is always encrypted and an easy way to get certificates.

Governments are already involved in cybersecurity. The question really is how involved with they get with IoT security. If the people who need to do things aren’t doing them, either we have the wrong incentive model and need to find the right one, or it is likely that governments will get heavily involved. It’s important that not happen until the technical community has some understanding as to the answers of these questions, and that may take some time.

Governments are already involved in cybersecurity. The question really is how involved with they get with IoT security. If the people who need to do things aren’t doing them, either we have the wrong incentive model and need to find the right one, or it is likely that governments will get heavily involved. It’s important that not happen until the technical community has some understanding as to the answers of these questions, and that may take some time. It’s a common belief that

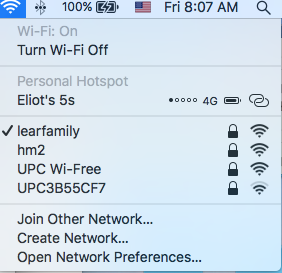

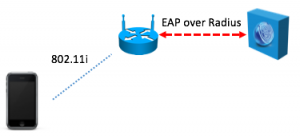

It’s a common belief that  What’s the right way to connect a Thing to your home network? Way back in the good old days, say last year, in order to connect a device to your home network, you could do it easily enough because the system had a display and a touch screen or a keyboard. With many Things, there is no display and there is no keyboard, and some of the devices we are connecting may themselves not be that accessible to the home owner. Think attic fans or even some light bulbs. A means is needed first to tell these devices which network is the correct network to join, and then what the credentials for that network are. In order to do any of this, there needs to be a way for the home router to communicate with the device in a secure and confidential way. That means that each end requires some secret. Public key cryptography is perfect for this, and it is how things would work in the enterprise.

What’s the right way to connect a Thing to your home network? Way back in the good old days, say last year, in order to connect a device to your home network, you could do it easily enough because the system had a display and a touch screen or a keyboard. With many Things, there is no display and there is no keyboard, and some of the devices we are connecting may themselves not be that accessible to the home owner. Think attic fans or even some light bulbs. A means is needed first to tell these devices which network is the correct network to join, and then what the credentials for that network are. In order to do any of this, there needs to be a way for the home router to communicate with the device in a secure and confidential way. That means that each end requires some secret. Public key cryptography is perfect for this, and it is how things would work in the enterprise.

Many in the tech community are upset over reports from The New York Times and others that

Many in the tech community are upset over reports from The New York Times and others that