The breach of over 500 million accounts at Yahoo! has caused a number of my friends to deride the company for not applying sufficient protections of private consumer data. While it’s hard to argue with that claim, one thing is certain: this will happen again. Maybe not to Yahoo! but to some other giant web site, like Amazon or Facebook or Google or Twitter.

The breach of over 500 million accounts at Yahoo! has caused a number of my friends to deride the company for not applying sufficient protections of private consumer data. While it’s hard to argue with that claim, one thing is certain: this will happen again. Maybe not to Yahoo! but to some other giant web site, like Amazon or Facebook or Google or Twitter.

We have concentrated so much trust into so small a percentage of sites that if any one of them has a breach, it can impact hundreds of millions of people. Americans have previously spoken of banks that are too big to fail. Social networking sites are similarly so big that when they have an incident, it perturbs our lives in all sorts of ways that we only begin to understand after the fact.

These sites have an interest in maintaining their customer interest, and the network effect helps them: the more people who visit Facebook, the more people Facebook will attract. This is how the Internet and telephone networks came to be in the first place.

This vast concentration of consumers into a small number of sites also has its upsides: because they are regularly attacked, they have developed very strong expertise to fend off bad guys. That’s something the average consumer – and even most enterprises – will never have.

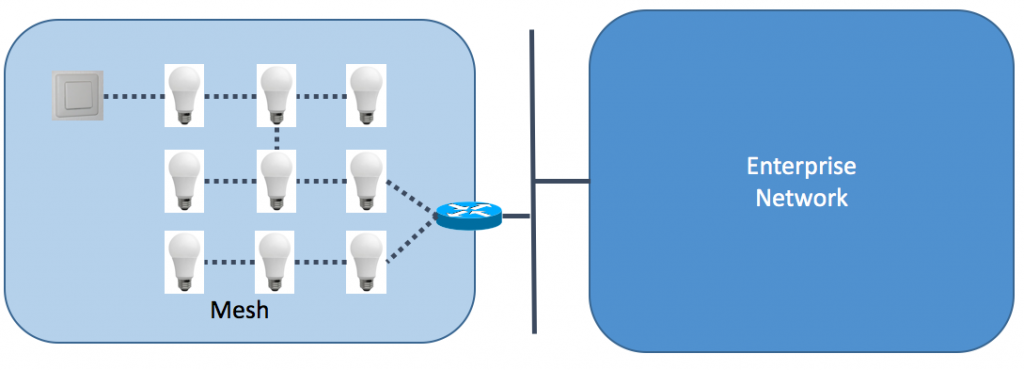

This form of market concentration is not an easy problem to solve. Imagine a world in which we all had software that sat on in our homes instead of in Facebook’s cloud (for instance). If the software were all the same, then one bug would impact everyone in much the same way as if the software were centrally located. The only question is how long it would take for an exploit of a vulnerability to propagate, and how long it would take someone to notice.

We know that such distributed software is a problem because one of the key vectors for infection these days is unused and out of date virtual machines or WordPress instances. This puts aside all the issues of cost of maintaining a WordPress site. How much does it cost you to maintain your Facebook account today?

One approach would a healthy exchange of social information across a reasonable number (perhaps in the thousands) of well managed sites. That requires a rethink about how we consider privacy and who is responsible. It also requires that incentives be aligned for that sharing to occur. We would in essence be suggesting that Facebook advertisers go elsewhere. That doesn’t seem like something Facebook would want to see.