When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top: Apple. Apple’s business model for iOS has been repeatedly demonstrated to provide superior security results over its competitors. In fact, Apple’s security model is so good that governments feel threatened enough by it that we have had repeated calls for some form of back door into their phones and tablets. CEO Tim Cook has repeatedly taken the stage to argue for such strong protection, and indeed I personally have friends who I know take this stuff so seriously that they lose sleep over some of the design choices that are made.

When we talk about secure platforms, there is one name that has always risen to the top: Apple. Apple’s business model for iOS has been repeatedly demonstrated to provide superior security results over its competitors. In fact, Apple’s security model is so good that governments feel threatened enough by it that we have had repeated calls for some form of back door into their phones and tablets. CEO Tim Cook has repeatedly taken the stage to argue for such strong protection, and indeed I personally have friends who I know take this stuff so seriously that they lose sleep over some of the design choices that are made.

And yet this last week, we learned of a vulnerability that was as easy to exploit as to type “root” twice in order to gain privileged access.

Wait. What?

Ain’t no perfect.

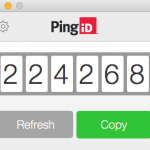

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from Ping Identity, a company whose job it is to provide secure access. This simple application that generates cryptographically generated sequences of numbers to be used as passwords is over 70 megabytes, and includes a complex Java runtime environment (JRE). How many bugs remain hidden in those hundreds of thousands of lines of code?

If the best and the brightest of the industry can occasionally have a flub like this, what about the rest of us? I recently installed a single sign-on package from Ping Identity, a company whose job it is to provide secure access. This simple application that generates cryptographically generated sequences of numbers to be used as passwords is over 70 megabytes, and includes a complex Java runtime environment (JRE). How many bugs remain hidden in those hundreds of thousands of lines of code?

Now enter the Internet of Things, where manufacturers of devices that have not traditionally been connected to the network have not been expert at security for decades. What sort of problems lurk in each and every one of those devices?

It is simply not possible to assure perfect security, and because computers are designed by imperfect humans, all these devices are imperfect. Even devices that we believe are secure today will have vulnerabilities exposed in the future. This is one of the reasons why the network needs to play a role.

The network stands between you and attackers, even when devices have vulnerabilities. The network is best in a position to protect your devices when it knows what sort of access a device needs to operate properly. That’s your washing machine. But even for your laptop, where you might want to access whatever you want to access, whenever you want to access it, through whatever system you wish to use, informing the network makes it possible to stop all communications that you don’t want. To be sure, endpoint manufacturers should not rely solely on network protection. Devices should be built with as much protection as is practicable and affordable. The network provides an additional layer of protection.

Endpoint manufacturers thus far have not done a good job in making use of the network for protection. That requires a serious rethink, and Apple is the posture child as to why. They are the best and the brightest, and they got it wrong this time.

Last year,

Last year,

[Updated thanks to an old friend.]

[Updated thanks to an old friend.]