Parents often seek the security of a baby monitor to know that their child is resting comfortably. Unfortunately that security is often misplaced. Last year Rapid7 produced a damning report, exposing numerous vulnerabilities in these devices. As an example, the Philips In.Sight B120/37 made use of a fixed password over an insecure telnet or web service that resides on TCP port 8080.

Parents often seek the security of a baby monitor to know that their child is resting comfortably. Unfortunately that security is often misplaced. Last year Rapid7 produced a damning report, exposing numerous vulnerabilities in these devices. As an example, the Philips In.Sight B120/37 made use of a fixed password over an insecure telnet or web service that resides on TCP port 8080.

The thing is- the In.Sight came very close to getting right, or as the great Maxwell Smart would say, “Missed it by that much!” That’s because Philips also offers a cloud-based service that would not otherwise require the device to listen to any TCP port. That’s a good way to go because it is harder to probe the device for vulnerabilities.

The thing is- the In.Sight came very close to getting right, or as the great Maxwell Smart would say, “Missed it by that much!” That’s because Philips also offers a cloud-based service that would not otherwise require the device to listen to any TCP port. That’s a good way to go because it is harder to probe the device for vulnerabilities.

One good reason to offer a local service is that some some people do not trust cloud services, and they particularly do not trust cloud services involving images of their children. Indeed this makes for a very difficult choice, because that same Rapid7 report notes problems with some cloud based services, and so parents wouldn’t be wrong to worry.

Either way, I’ve built a MUD file using MudFileMaker.

A brief view of the application alongside tcpdump together with a quick view of the server binary seems to indicate that cloud communications are to api.ivideon.com. We can thus come up with an appropriate MUD file as follows:

{

"ietf-mud:meta-info": {

"lastUpdate": "2016-10-03T12:56:08+02:00",

"systeminfo": "Philips In.Sight B120/37 Baby Monitor",

"cacheValidity": 1440

},

"ietf-acl:access-lists": {

"ietf-acl:access-list": [

{

"acl-name": "mud-94344-v4in",

"acl-type": "ipv4-acl",

"ietf-mud:packet-direction": "to-device",

"access-list-entries": {

"ace": [

{

"rule-name": "clout0-in",

"matches": {

"ietf-acldns:src-dnsname": "api.ivideon.com",

"protocol": 6,

"source-port-range": {

"lower-port": 443,

"upper-port": 443

}

},

"actions": {

"permit": [

null

]

}

},

{

"rule-name": "entin0-in",

"matches": {

"ietf-mud:controller": "http://ivideon.com/babymonitors",

"protocol": 6,

"source-port-range": {

"lower-port": 8080,

"upper-port": 8080

}

},

"actions": {

"permit": [

null

]

}

}

]

}

},

{

"acl-name": "mud-94344-v4out",

"acl-type": "ipv4-acl",

"ietf-mud:packet-direction": "from-device",

"access-list-entries": {

"ace": [

{

"rule-name": "clout0-in",

"matches": {

"ietf-acldns:src-dnsname": "api.ivideon.com",

"protocol": 6,

"source-port-range": {

"lower-port": 443,

"upper-port": 443

}

},

"actions": {

"permit": [

null

]

}

},

{

"rule-name": "entin0-in",

"matches": {

"ietf-mud:controller": "http://ivideon.com/babymonitors",

"protocol": 6,

"source-port-range": {

"lower-port": 8080,

"upper-port": 8080

}

},

"actions": {

"permit": [

null

]

}

}

]

}

}

]

}

}

Remember, the router needs to fill out which devices are authorized to be in class http://ivideon.com/babymonitors. Note the use of incoming tcp port 8080. It is possible at least for the server software run on another port if the configuration is changed. At that moment, the above MUD file would be too restrictive, and the device would not function. To fix that, one would simply remove the TCP port filter.

Again, note that only authorized communications are listed in the file, and so just because the developer left a telnet server in place doesn’t mean that just anyone would be able to access it. This serves as a means to confirm the intentions of the developers. Of course developers should never leave back doors, but if they do, perhaps MUD can reduce their impact, and let parents rest just a little easier.

When Edward Snowden disclosed the NSA’s activities, many people came to realize that network systems can be misused, even though this was always the case. People just realized what was possible. What happened next was a concerted effort to protect protect data from what has become known as “pervasive surveillance”. This included development of a new version of HTTP that is always encrypted and an easy way to get certificates.

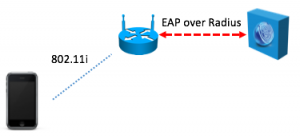

When Edward Snowden disclosed the NSA’s activities, many people came to realize that network systems can be misused, even though this was always the case. People just realized what was possible. What happened next was a concerted effort to protect protect data from what has become known as “pervasive surveillance”. This included development of a new version of HTTP that is always encrypted and an easy way to get certificates. What’s the right way to connect a Thing to your home network? Way back in the good old days, say last year, in order to connect a device to your home network, you could do it easily enough because the system had a display and a touch screen or a keyboard. With many Things, there is no display and there is no keyboard, and some of the devices we are connecting may themselves not be that accessible to the home owner. Think attic fans or even some light bulbs. A means is needed first to tell these devices which network is the correct network to join, and then what the credentials for that network are. In order to do any of this, there needs to be a way for the home router to communicate with the device in a secure and confidential way. That means that each end requires some secret. Public key cryptography is perfect for this, and it is how things would work in the enterprise.

What’s the right way to connect a Thing to your home network? Way back in the good old days, say last year, in order to connect a device to your home network, you could do it easily enough because the system had a display and a touch screen or a keyboard. With many Things, there is no display and there is no keyboard, and some of the devices we are connecting may themselves not be that accessible to the home owner. Think attic fans or even some light bulbs. A means is needed first to tell these devices which network is the correct network to join, and then what the credentials for that network are. In order to do any of this, there needs to be a way for the home router to communicate with the device in a secure and confidential way. That means that each end requires some secret. Public key cryptography is perfect for this, and it is how things would work in the enterprise.

Many in the tech community are upset over reports from The New York Times and others that

Many in the tech community are upset over reports from The New York Times and others that  Parents often seek the security of a baby monitor to know that their child is resting comfortably. Unfortunately that security is often misplaced. Last year

Parents often seek the security of a baby monitor to know that their child is resting comfortably. Unfortunately that security is often misplaced. Last year  The thing is- the In.Sight came very close to getting right, or as the great Maxwell Smart would say, “Missed it by that much!” That’s because Philips also offers a cloud-based service that would not otherwise require the device to listen to any TCP port. That’s a good way to go because it is harder to probe the device for vulnerabilities.

The thing is- the In.Sight came very close to getting right, or as the great Maxwell Smart would say, “Missed it by that much!” That’s because Philips also offers a cloud-based service that would not otherwise require the device to listen to any TCP port. That’s a good way to go because it is harder to probe the device for vulnerabilities. In the attack against

In the attack against